Introduction

Back in November 2023, I got the news that I had been selected as one of the recipients of the Yukon 125 prize. The purpose or intent of this ‘prize’ was relatively vague but the gist was that the Yukon was celebrating it’s 125 years of being a part of Canada in June 2023. A number of initiatives were marking the occasion and the Yukon 125 prize, led by the Tourism & Culture department of the Yukon Government, was giving away a pot of $250,000 to ‘innovative and bold’ projects that would showcase something cool about the territory to encourage visitors.

This was an obvious and unique opportunity to get a climbing expedition fully funded, as well as having an excuse to flex some creative muscles while doing it. Particularly unique in this regard since many people who do these types of expeditions will tell you that it’s incredibly rare to find a singular sponsor who will cover all expenses. High-end climbers fight tooth and nail to get a small portion of their expeditions funded by the common grants. Only in the Yukon would a climber as mediocre as me have this sort of opportunity.

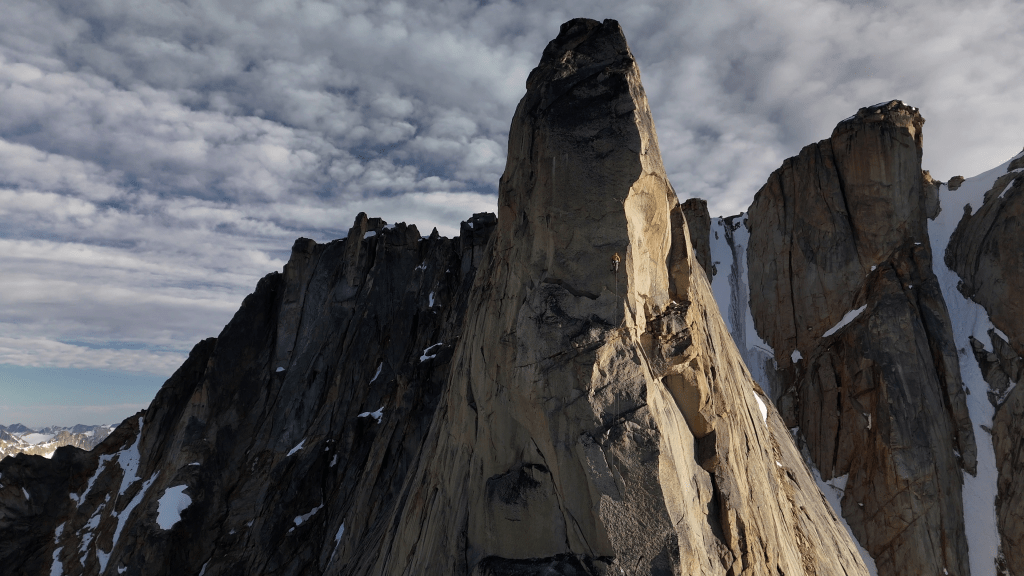

As I went through the various phases of the application, the objective went from a handful of options to eventually landing on Radelet Peak in Southern Yukon, culminating in my final video submission. It was an obvious choice since I was in talks with Zach Clanton about being the other initial member of the team. Zach had spent 28 days in the area attempting a climb up the ‘Crystal Tower’, the obvious king line to the main summit of the multi-peaked massif. Zach and his partners flew in to a nearby lake via floatplane, triple carried gear over a week, and got up two pitches before bailing because of scary, unprotected rock. It was clear that this area, while being made up of desirable granite spires, would require a more modern approach, climbers armed with power drills. Well, that or be an incredibly bold and strong climber. We brought drills.

With such a flexible form of funding available, it was the perfect opportunity to attempt to open the climbing in this zone. Without it, we would not be able to afford the multiple helicopter trips it took to ferry in our ridiculously high-tech, and high-weight, basecamp. Complete with two solar power systems to recharge our drills, Zach’s drone and camera, 60 expansion bolts, 5 ropes with various uses, personal camping and climbing gear, and 22 days worth of proper meals. The two short weeks we had booked in the area could have easily been taken up by the simple act of manually carrying all of this in. Without funding from Yukon125, none of this could have been accomplished.

The Crew

John

Let’s start off with myself. I’m 29, the youngest on the trip. I’m a weekend warrior who works in climate change mitigation/adaptation, I’ve lived in the Yukon for 3 years. I’ve been a climber for a little over 6 years. Ever since I started, I’ve aspired to climb new routes, particularly in the alpine, and I’ve dedicated my time to building those skills. The Yukon has allowed me to live in an area with so much potential for new climbing routes and it’s been a pursuit of mine since coming here. I’ve really enjoyed developing moderate multipitch routes to help build a path for newer Yukon climbers to gain skills for adventure climbing, such as Let Them Eat Cake and Agents of Entropy.

Rob

Rob, or Robbo as he’s known in his homeland down under. He’s been climbing for 10 years all over Australia and Western Canada, mostly traditional climbing. He’s spent many years in the Yukon and recently graduated from Yukon University with a diploma in Northern Sciences. He’s known around town as Rob Bicycle for his dedication to commuting in the lowest impact way he can, no matter the weather. He and I developed Agents of Entropy and have climbed all sorts of adventurous trad routes in the Yukon together.

Zach

Zach is the quintessential over-stoker dirtbag. He lives out of his truck camper with his extremely cute dog Yote and chases the climbing season all over his home country, good ol’ Murica, though he’s largely been based out of SE Alaska since 2012. He funds his lifestyle by being a kickass photographer and videographer with an impressive resume, working with brands like Arc’teryx and BBC. All one has to do is type his name into the American Alpine Journal archives to see a long list of impressive first ascents up big routes in Alaska, BC, and Mexico.

Dave

Dave was the last minute addition that ended up working incredibly well despite the ‘blind date’ format. Dave’s wealth of knowledge and experience proved to be a major asset to the team and is almost impossible to summarize. He has been climbing for 36 years, from difficult sport climbs to big walls to new routes in the Himalaya to the first ascent of the most celebrated alpine rock climb in the territory; Reflection Ridge on Ark Mountain. He’s a career teacher, a family man, and all around outdoorsman who spends his time gardening, bird watching, hunting, building, and, of course, climbing.

THE LAND

Radelet (etymology unknown as of yet) or ‘The Crystal Towers’ is a massif of granite spires and peaks in Southern Yukon, just above the BC border, sitting in the Coast Range, which stretches from its southern terminus in Baja Mexico to not much further North than the peak in question. This section of this massive range is known as the ‘Boundary Range’, following the borders of SE Alaska, BC, and the Yukon.

It’s main summit reaches a modest altitude of just over 2500m but the relief of it’s largest features is over 500m from the glaciers that sit in it’s cirques. These glaciers are the headwaters of the Wheaton river, a watershed that is a well known destination for local paddlers and hikers. Determined recreationists have made the trip into this beautiful area before. To find your way here without flight requires one to follow the Annie Lake road, through creeks where now dismantled bridges used to provide passage, and deep into a mining exploration road piercing the alpine. Then, a steep hike from the end of the road takes one up and over a high alpine pass and into the ‘Upper Wheaton’, which can be followed to the glacier just under the main summit’s rocky buttress, known as ‘The Crystal Tower’.

It is the traditional territory of the Carcross-Tagish First Nation, who travelled the trails passing alongside the Wheaton from Carcross (Nadashaa Héeni), presumably part of the network of ‘grease trails’ and used for access to hunt sheep and caribou amongst the many craggy peaks of the Wheaton watershed and Boundary range.

Our camp was made on the banks of a glacial lake in the cirque to the east of the summit and bordering our objective. Presumably an old glacial moraine, covered in granite of varying stages of decomposition. From sand to weathered rocks to some of the most solid, clean granite boulders you’ll ever find (often, the solid and weathered rock would coexist on the same boulder). The most astounding part of the geology in the area is the eponymous quartz crystals found amongst the talus. Zach found a smoky quartz crystal the size of a mini football on the first day.

Wildlife was almost non-existent on our trip. Only water-borne insect casings in the just melting water of the lake, a handful of birds, and the sighting of a ram from far away. There was plenty of lichen though with scattered patches of moss, grass, and even some tiny leafy shrubs. Perhaps the landscape was just too ‘new’? Or a typical case of Yukon desolation. It is not uncommon to find yourself alone in these Northern valleys.

Climbing History

As mentioned, local indigenous peoples have had a presence in this area for upwards of tens of thousands of years. To this day holding an in-depth relationship in the Wheaton Watershed for the purposes of subsistence and recreation.

The area is also hardly an unknown to local and visiting recreationists. There are various reports of skiing, hiking, and mountaineering in the area over the most recent decades. NOLS Yukon has hiked the main summit via the easy backside, local climbers established ice climbs up the central gully to the left of the Crystal Tower in the 90s (repeated by local guide, Eliel, who then skied it), Eliel also guided another ice climb to the right of the main gully, professional skiers have even visited to ski the gnarly couloirs amongst the spires as a warm-up to skiing big spine lines in Haines Pass (seen in the film Tsirku), Zach and his partners were awarded a grant to attempt a climb up the Crystal Tower in 2018, and numerous other reports of hikers/skiers exploring the area, including a semi-viral Youtuber who hiked the peak with his tiny dog, Rocco.

The Climb

July 1

It took two trips in a Long Ranger flown by our pilot Max from Capital Helicopters to get all four of us and our gear delivered. The first team (Zach and Dave) flew in from Whitehorse. Rob and I met Max in Carcross where he refueled and flew us the 50km west to basecamp. Once all of us were down on relatively solid ground, we quickly established the first of many iterations of our camp.

Dave was loathe to waste nice weather and so we all decided to check out the approach to the start of the route. We hiked the talus field for about half an hour to the obvious col above the lake, portering our first loads of gear. It turned out to be relatively straightforward, contouring along a steep talus slope and culminating in a short section of 4th class scrambling to top out on the broad start of the ridge.

Dave and Zach ro-sham-bo’d for the honour to lead the first pitch. They both threw rock the first four times (surely some sort of unconscious bias) but eventually Dave prevailed. The pitch turned out to be a bit more than he bargained for and he made the mistake of underestimating it, choosing to climb without a drill, forced to au cheval the final knife ridge section completely unprotected and belay Zach, carrying the drill, up to his stance at a less than ideal gear anchor.

The first sight of the ridge from the col just shattered my mind.

– Robbo

The horizontal nature of the route’s beginning took us all by surprise. Pitches that appeared to be straightforward and short turned out to be complicated and rope stretching. Most of the climbing was relatively easy but rock quality wasn’t always perfect, often lichen covered, and we contended with cold and windy conditions for the vast majority of the trip. I fully intended to help lead pitches on the route. Rob and I established the 7 pitches of Agents of Entropy, bolting ground up on lead, as a training exercise for Radelet. But the conditions, the instant and often dizzying exposure, and complexity of the route naturally delegated the less confident Rob and I to supporting roles for Dave and Zach.

July 2

We fell into a natural rhythm of shift-work. Two teams of two leapfrogging their way up the route. 1 day on, 1 day off. The second day, Zach and I established pitch 2 while Dave re-routed the fixed rope on pitch 1 to a better protected, but still complex, alternative that would make it easier to ferry supplies to the high point. A right facing corner below the knife edge section. One would have to rappel off a gear anchor, clip in direct to a bolt, switch their GriGri around, and ascend to the first anchor. Often carrying heavy loads for the high point. But it beat trying to hump your way across the sharp ridge with the same burden.

Pitch 2 was easy from a free climbing perspective but began with a series of dangerous blocks perched on the ridge above. Zach chose to bypass these via a rightward curving traverse on a lichen covered slab, doing a mix of free and aid between the 3 bolts he placed to then regain the ridge. This pitch was evidence we had not dialed our systems as a team. The half ropes that Zach brought were brand new and the kinks had, quite literally, not yet been worked out. Belaying him with my Gigajul turned out to be almost impossible as the ropes twisted around each other and the tag line, making it nearly impossible to unlock the assisted braking mode and feed rope simultaneously. Despite re-coiling several times, the belay stance was awkward and the 3 ropes were difficult to handle. I fought for every inch of slack and he eventually reached a natural belay stance 60m away. We brought a rope up to fix, left gear at this new high point, and cleaned the dangerous blocks on rappel. This allowed the pitch to go directly up the ridge on easy but unprotected terrain, if repeat climbers so wished.

Oh, my [taint] is f’d

– Unnamed team member after Au Cheval’ing the knife edge

July 3

The next day was a rest day for Zach and I. But with the midnight sun at this latitude, 60 degrees N, Rob and Dave weren’t in a rush to get on the route. Rob and I did a scouting hike early in the day to the base of some of the smaller towers on the south side of the massif and we finished the move to Rob’s recently renovated ‘kitchen site 2.0’.

At around 6pm, Dave and Rob headed up the approach talus to push the route a little higher, establishing the third pitch. Another ~45m to a well protected belay in a little alcove.

July 4

Zach and I took our turn, heading up the fixed lines to the highpoint on pitch 3 carrying the final 90m static rope, with approximately 45m of unused line coiled at the highpoint. Though the belay was nicely sheltered (from wind and falling rock) it was cramped and there was a lot of gear hanging between the two bolts of the anchor. Dave had flaked the half ropes into a dry bag and I chose to belay with the Gigajul in tube mode, which vastly improved the belaying experience. However, miscommunication about the plan with the fixed lines led to some issues when we hadn’t learned our lesson about the appearance of the length of pitches. Unbeknownst to me, the tag line was only 60m with our lead lines being 70m. Furthermore, Dave had not left my ends of the half ropes out so that I could tie in pre-emptively. Zach stretched the ropes to their max and I had to suddenly scramble to tie the tag line to the static rope before it flew from the belay. I chose the wrong one, then was quickly faced with trying to secure enough tail in the end of the halves so I could tie myself in to follow. Because of this mishap with the static line, once Zach had bolted the belay, we ended up in a complicated situation with me climbing up and down to rectify the fixed line set-up.

Eventually, I followed with the haulbag full of gear on my back, and was stoked on the proper climbing on this pitch. A fin of rock protruding from the ridge provided a ‘Skywalker‘-esque corner to layback and jam up. Followed by a series of finger cracks and slabs (that we later split into a separate pitch) to the base of what Zach was calling the ‘gnar step’.

The Gnar Step was the first properly vertical (or overhanging, really) step on the ridge. This route seemed persistent on messing with our minds and the step, though appearing from afar to be one of the larger features on the route, only turned out to be about 15m.

We were amazed to find a splitter crack running up the middle, providing reasonable looking access through the steep feature, beginning with fingers up well featured slab before turning to a hand crack in a steep corner. The wind began to pick-up and things were much colder, so Zach went from free climbing up the finger crack to aid climbing the steep hands section, cleaning some small chockstones while he went. Though he aided the section, he saw obvious features that suggested freeing the whole pitch would likely happen at somewhere in the 5.10 range.

July 5

We all struggled to sleep with gusting wind that persisted throughout the night and into the morning. Most of the valley was socked in when I got up to relieve myself, so I slept in, assuming that everyone else was doing the same, but woke to Rob calling to me at around 11am. He and Dave were headed up to the route to see if they could get anything done. I was shocked they would even consider it in the conditions but apparently they just kept moseying along with a thought of “We may as well keep going and see how it is when we get there” until they found themselves at the high point above the Gnar Step. They repeated the logic internally and pressed forward.

We called the next feature the ‘Black Slab’ or the ‘Triangle Slab’. For obvious reasons. It started with a short, low 5th apron pitch to reach the base of the steeper section. Rob and Dave established an exposed belay here, looking down on the incredibly steep SE face of the ridge. Dave attempted to lead the next pitch, battling wind, a bit of snow, and frozen fingers in thin cracks. He eventually reached a section of lichen covered slab that he justifiably did not feel compelled to aid his way up in the existing conditions and decided to place an intermediate anchor and descend.

I wish I was back in Australia with my girlfriend.

– Robbo, top of the gnar step

July 6

A welcome rest day for all. Rob and I did another scouting hike. We contoured down the slopes of the moraine into the valley below, finding some easy looking single pitch potential for future rest days. We passed the base of the Broken Slabs, seen from my tent every day, and found surprisingly fantastic and well featured rock. Then scrambled up a gully between the Broken Slabs and what I called ‘Picnic Tower’, eating lunch inside a large cave roofed by a massive chockstone. We moved upward to another small cave and I chose to continue up a short 4th class step to gain the upper section of the gully to scout a potential, hopefully short and moderate, route to the summit of the tower. Rob hung out in the cave, sheltered from my falling debris. After my foray, I found an amazing tall-boy can sized smokey quartz crystal on the descent.

That evening came discussion about the plan for the route. We had established 7.5 pitches and the fixed ropes had run out. The next day we would go for the summit push.

Only bringing 2 rolls of toilet paper per person might have been a mistake…

– John, Day 1

July 7

The big day. The conditions for the foreseeable future were looking poor and we were out of fixed ropes. The choice was obvious, we might not have another chance to make a summit push. The plan was that Zach and I would head up first to push the highpoint and Dave would follow while cleaning some of the lower fixed ropes and bring them up to the highpoint, in case it looked like the route would need more work.

The first crux of the day was jugging the Gnar Step. Thankfully we had a beefy static line with a rope protector on the sharp edge of the step but it was my first time ascending an overhanging fixed line. Honestly, it felt like it might have been more effort than simply TR soloing the pitch but c’est la vie. I often found myself spun around looking straight out at the exposed drop below but tried to focus on what was right in front of me, passing the rope protector and the lip was incredibly awkward but soon enough Zach and I made it to the belay at the base of the black slab.

Dave had set up the half ropes to top rope off but it was a slightly janky set-up, with the two ropes tied together, presumably this was just how it ended up when he rapped from the intermediate anchors. But to lead the final section of the pitch required Zach to TR to the highpoint then pull the other rope’s end back up and tie-in. It all worked out but was a bit of a mess-around and took some time. Zach led up the slab with a mix of free and aid, placing three protection bolts then running it out on the exposed arete to the base of the ‘second step’. He pulled up one of the static ropes to fix and I jugged with some gear necessary for the next pitch, followed by Dave who hauled a bag with some food, water, and Zach’s camera gear.

The next pitches were a big question mark. There was an obvious traversing crack right, by-passing the steep second step, but the rock was a bit suspect. Then we’d have to find our way up some cracks/chimneys to the base of the final headwall. The traverse pitch was shorter than it looked from Zach’s drone scouting and definitely had some manky rock but thankfully there was enough solid stuff to place bolts for protection. Right before the end of the short pitch though, there was a huge block. It felt solid but we definitely avoided pulling on it, which was quite difficult as you had to essentially bear hug it while grabbing rock on either side. But eventually we all made it to the next belay.

Though we were at a nice big ledge, the nature of the next pitch definitely required the belayer to take shelter. Thankfully, there was a little roof/alcove that allowed me to be fairly sheltered. However, there was not a lot of room with Dave and all the gear, so parts of me were sticking out. It was also incredibly uncomfortable to belay in a squatted down position trying to bury my head below the roof. Many large chunks of rocks hit where the natural stance of a belayer would be, based on the anchor bolts, even though it was off to the left of the main pitch. Eventually, Dave saw the predicament here and helped move around the gear and himself so that I could fully cover myself under the roof. Still, it was awkward and uncomfortable, but I felt a bit safer.

We found out later by looking at Zach’s old pics of this pitch that a massive, VW bus sized boulder had clearly fallen off this section in the last few years and left a significant amount of loose rock behind. Though much of the pitch was fine quality rock, the top out (and naturally the chimney) had some good sized chunks. Thankfully, not much proper chimneying was necessary as Zach was able to do some face climbing to the left of it.

Zach topped the pitch and bolted the next anchor. He was ready to hand off the lead to Dave, so Dave tied into the lead lines and followed. Zach attempted to haul the bag up with the tag line but it predictably was caught. Not a problem, I’d jug and free it as it went. Though it was not nearly as smooth as we had hoped. Firstly, there was significant chunks of rock that needed to be trundled at the next belay ledge but I was forced to jug with the rope running over them. Thankfully, Zach had placed a rope protector over the worst looking edge, but it was a jumble of broken boulders and there was no perfect solution. (We used the 4 hours that it took to belay the next pitch to trundle most of the blocks here and left the pitch in much safer conditions).

I reached the haul bag and freed it easily. They began hauling it hand over hand, clearly intent on leading the next pitch ASAP. This was a mistake. There was nowhere for me to hide and as the bag reached the lip of the belay ledge, where the worst of the loose rock was, it knocked a soccer ball sized rock off. Dave shouted and I was able push off the wall just in time and dodge it, right as it flashed past my previous position. I’m not sure the damage it could have done, it had not been in flight long enough to gain terminal velocity, but at a minimum it would have hurt badly if it made contact. At worst, if it hit me square in the head? Who knows. It shook me and I yelled at them to stop pulling the bag until I was able to finish jugging.

I reached the belay at the base of the final step/headwall around 6:45pm, after leaving camp at 9am. The winds had picked up, I was cold, tired, hungry, and shaken from what had just happened. At this point, I really didn’t care about the route but we were so close. I resigned that, unless the jugging on the next pitch was straightforward, this would be my highpoint.

Dave had already started leading the next pitch, aiding a steep crack to the left of the belay. Above was an epic left-leaning serrated crack that looked relatively moderate. Unfortunately, it had an equally serrated flake sticking out of it, threatening to cut us in half if a climber were to knock it out. This looked like an easier alternative to what Dave was doing, but future climbers will have to trundle that flake from above first.

After pulling the lip of the crack, Dave started aiding off bolts through a featured face climbing section. It looked easily freeable but Dave was climbing in boots and multiple layers, not the time for it.

He eventually reached the feature Zach called ‘the maw’. A massive crack splitting horizontally across the headwall. He was excited to find what looked like a perfectly sheltered, flat bivvy spot in it. This was an obvious belay spot and he shouted down that he was tired and would prefer a swap in leads. Even though he hadn’t been leading until now, he had been working extremely hard bringing up the fixed ropes and his fatigue was totally justifiable. Zach convinced him it would just add more unnecessary time to do a swap. There was plenty of rope for Dave to continue the lead but the drag was terrible. He decided to anchor in direct clipping his last bolt and slinging a horn on the maw crack. He untied and we pulled the lead ropes down, out of the gear in the crack and face. He then hauled the ropes plus snacks, water, and the final 13 bolts we had up to his position and tied back in. The funny thing about these bolts was that most of them had rap hangers/rings on them. Presumably in an effort to save weight on lead, Zach had been establishing anchors with standard hangers with the expectation of us switching them out with rap hangers as we went. Dave had done a few but not all of them and so we were left with a handful of them for this final pitch to use as protection/aid.

Next came a challenging decision for the team given the position on the route and our fatigue. As I mentioned, I was resigned to stay put until the descent and Zach was insistent on Dave continuing his lead as fast as possible given the length of time we had already put into the push and what was going to be a long, complicated descent. Dave yelled down that he saw some other options but with our belay stance, the rope drag would be too great. The only option then was to aid his way up the headwall and hope the face climbing would lend itself to a possible free ascent in the future.

So, he went, placing a bolt, then drilling hooks up the slightly overhung sheet of granite, then placing another. Until he ran out of hardware at the lip of the headwall.

When you look at the ridge in question, there are two obvious highpoints. The main summit (which is not actually the summit of Radelet but just another highpoint on the massif) and the sub-summit or ‘horn’, just above the top of the headwall. We agreed that reaching this horn constituted enough of a high point of the main feature we were climbing to call it an established route. It is undeniable that nobody on our team stood atop this ‘highpoint’. However, Dave was certain in his ability to bellyflop up onto that final ledge above the steep climbing, followed by a short section of easy climbing to reach the top of the horn. What he was less certain of was his ability to find an anchor to descend with no bolts and his ability to safely downclimb in boots to his last bolt if he was unable to find a natural anchor. So, he chose to descend from this last bolt, leaving the one below it clipped as a back-up.

Does this mean we ‘failed’ in our attempt to establish the first ascent of this feature? I suppose that’s up for interpretation. Dave seems satisfied with calling it a ‘send’ given the circumstances and with his immense experience, I’m inclined to agree. Or at least, we both seem inclined to not really care too much about the opinions of others. My main goal with the trip was to open the area up for future parties and we’ve clearly done that. Zach seems to be a bit more on the fence. He plans to return, with no bolts, and hopes to free the route and the final few easy looking pitches to the Main Summit. If Zach, or another party, make it to the Horn or the Main Summit and want to claim the proper First or Integral ascent, then I’m just happy we played a major part in making that happen and showing people the incredible alpine climbing potential in these lesser known, but spectacular, parts of the Yukon.

Dave finally returned to the belay at ~11pm. Over 4 hours after starting his lead on this final ~50m of climbing. To my immense relief, we began the descent. Despite all of Daves’ hard work bringing the fixed lines up to this high point, it was clear that nobody was going to muster the motivation to come all the way back up here with the marginal forecast we had and so we chose to bring them down, at least to below the Gnar Step.

We rappelled through the night with most of the descent going smoothly except the extremely awkward traversing pitch to the base of the second step. The ropes got stuck when we went to pull them and Dave re-led then down climbed the pitch to free them. During this time, this far north, there is no such thing as pitch black conditions. We found ourselves in a heavy dusk for a couple hours while we re-fixed the pitches below the Gnar Step, going through the motions until we suddenly were back at the col and walking to camp, stumbling in at 3:40am, almost 19 hours since we had left.

Rob was still up, having kept in contact with us via radio, and fed us tea and toasted bagels with cream cheese. The gale force wind had returned, we scarfed our meal down, and retired.

Post-Climb

July 8

The next day was another beautiful, but windy, day. It was only part of this two day weather window. Which none of us were in shape to do a 2 day push, so we enjoyed the sunshine and rested.

July 9

Though an overcast and windy day, it seemed to be the best option before the weather became properly cold and unstable, so Zach and Dave went up to clean the lower fixed lines as they hoped they might get a small window of calm weather to free the Gnar Step. They lucked out and were able to manage it, with Dave leading and Zach following, confirming a grade of 5.10-. Rob and I ferried supplies from the col back to basecamp.

July 10

Rain. Tent-bound most of the day. A massive rock slide came down to the left of our approach.

Our original pick-up date was July 15, with the forecast looking poor, we messaged the heli company and arrange a pick-up on July 12. The next two days looked to be cold but no rain, so we hoped we could get conditions to either climb on some of the smaller features around or hike to the peak of Radelet.

July 11

Cold and windy but no rain. Certainly was not climbing weather so Dave, Rob, and I decided to hike to Radelet summit via the easy backside. Zach chose to stay in camp and do some bouldering instead.

We contoured left around the lake and the SE face of the massif, up a 30-35 deg snow slope to a col, then a low-angle rising traverse to the main summit, which was socked in and windy. But we got enough intermittent clearings to see the astounding views to the south and west, deeper into the Boundary Range.

July 12

Our flight was booked for 6pm so we bummed around, getting our stuff prepped but not too prepped in case weather came in and stopped our exit.

The lake was finally open enough for Zach to take the maiden voyage on SS Flamingo and I filmed an interview with him for the short film I plan to make out of the trip, as part of the contract with Yukon 125. I turned off my inReach to avoid any errant sounds then turned it on 20 minutes later to see Max, the helicopter pilot, ready to pick us up early. The weather was relatively clear with a high ceiling so I gave him the go-ahead and we scrambled to finish the final packing. A snow squall came in shortly after sending the message and I updated him but received no response, I just hoped that it was still suitable conditions for flying.

His machine came suddenly roaring over the ridge to the NE of camp and he circled, feeling the wind out apparently. The weather cleared but there was still a drizzle and haze. He landed directly on his old skid tracks then exited to grab the first load with the rotors still running. Dave and I took the first ride out to Carcross. Even though it was sort of windy and overcast, we were the warmest we’d been in the last 12 days. It was more than 10 degrees warmer, the air smelled of the boreal forest and the ground was level. The next morning, I ate my lost weight back in greasy breakfast foods at the Legends diner in downtown Whitehorse.

The Future for the Crystal Towers

It’s hard to say exactly what the future is for this amazing area. Hopefully Zach gets back out there to establish the First Free Ascent of the route or someone else takes up the challenge if he is unable to. Once that is done, I believe the route will be considered a desirable Northern adventure climb. Up there with classics like the Lotus Flower Tower and Reflection Ridge.

Because of the mixed quality of the rock and the lack of sustained crack systems, it is hard to imagine anyone establishing new, safe routes in the area without the use of bolts. Which makes it very difficult to imagine anyone establishing new routes with a more affordable, human powered approach. Regardless, I believe there is plenty of opportunity for high-quality, alpine rock climbing on the massif. The cirque we inhabited was one of many, all the adjacent cirques and drainages have impressive rock features ready for first ascents. The Crystal Tower up to the main summit of Radelet Peak itself is one of the most obvious prizes for a well-prepared team.

Beyond climbing, Radelet is a scrambler’s and mountaineer’s paradise, with surprisingly easy alternative routes up many of the summits.

Photos: Zach Clanton (Click image for more information)

Route Beta

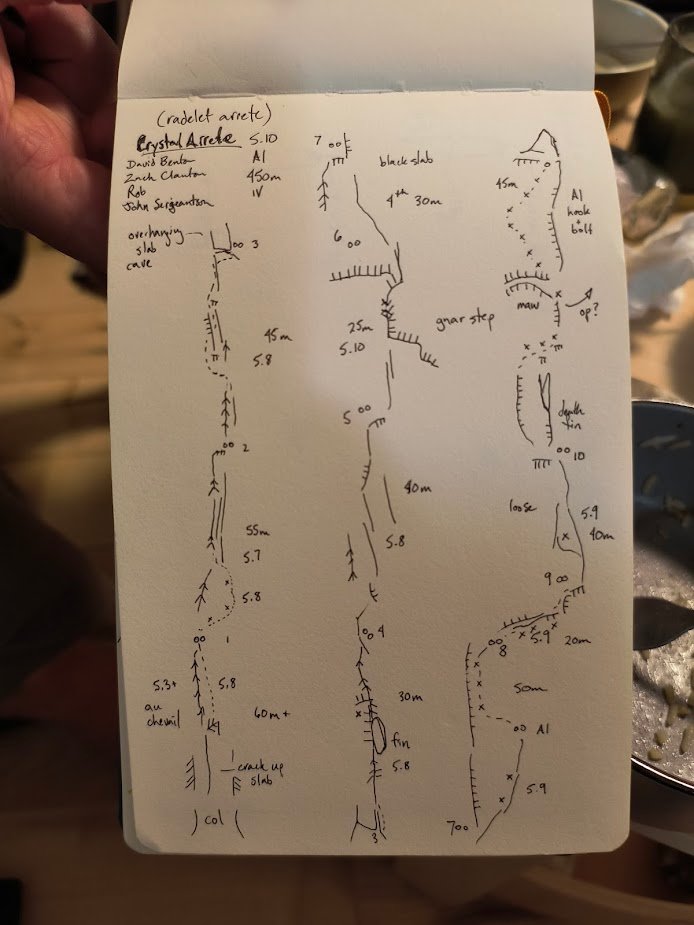

The route, in it’s current state, could easily be repeated by a team with no need for a drill or additional bolts, though that team should be prepared to aid on hooks in drilled holes between the bolts on the final pitch (or bring a collapsible stick clip). However, if you wanted to properly top out, a hand-drill and 2-3 bolts to be confident you can establish an anchor at the proper top of the sub-summit/horn wouldn’t be a bad idea either, lest you want to descend from our highpoint. Additionally, the anchors that did not have ring-hangers installed were connected via cord and we left carabiners to rap, so additional tat would be recommended (Or take the hangers as you go and replace the upper ring hangers, hah!).

Most of the pitches have gone free, or mostly free, on the handful of days we spent on the route. However, in many cases, such as where we were bolting on slab, or the final crack at the base of the headwall, aid was employed and those sections were never free climbed. Based on the features, we’re fairly confident that everything but the final bolt ladder will go free at 5.10 or below. As mentioned, when cleaning the fixed ropes, Zach and Dave sent the Gnar Step. Despite it being one of the steepest pitches on the route, they felt it was 10- and very well protected. The crack at the base of the Headwall was likewise quite steep but Dave feels it would be in the 5.10 range also. Regardless, it’s relatively short and was aided at C1. Highly recommended to bring a brush on the pitches with slab to clean the lichen off key holds. Overall, the line in it’s current state, was climbed at a grade of 5.10 A1.

If anyone reading has the hopes of doing more than just repeating our climb, such as trying to free the last pitch or climbing the whole ridge to it’s Main Summit, then I would highly recommend reaching out to Zach first, as he still views this as a project and has put a lot of time and effort into the area. Standard climbing ethics would give him right of refusal, as long as he still has solid plans to return and finish the project in the near future. For more specific beta, or to be connected with Zach, feel free to email me at: JSerjeantson@gmail.com

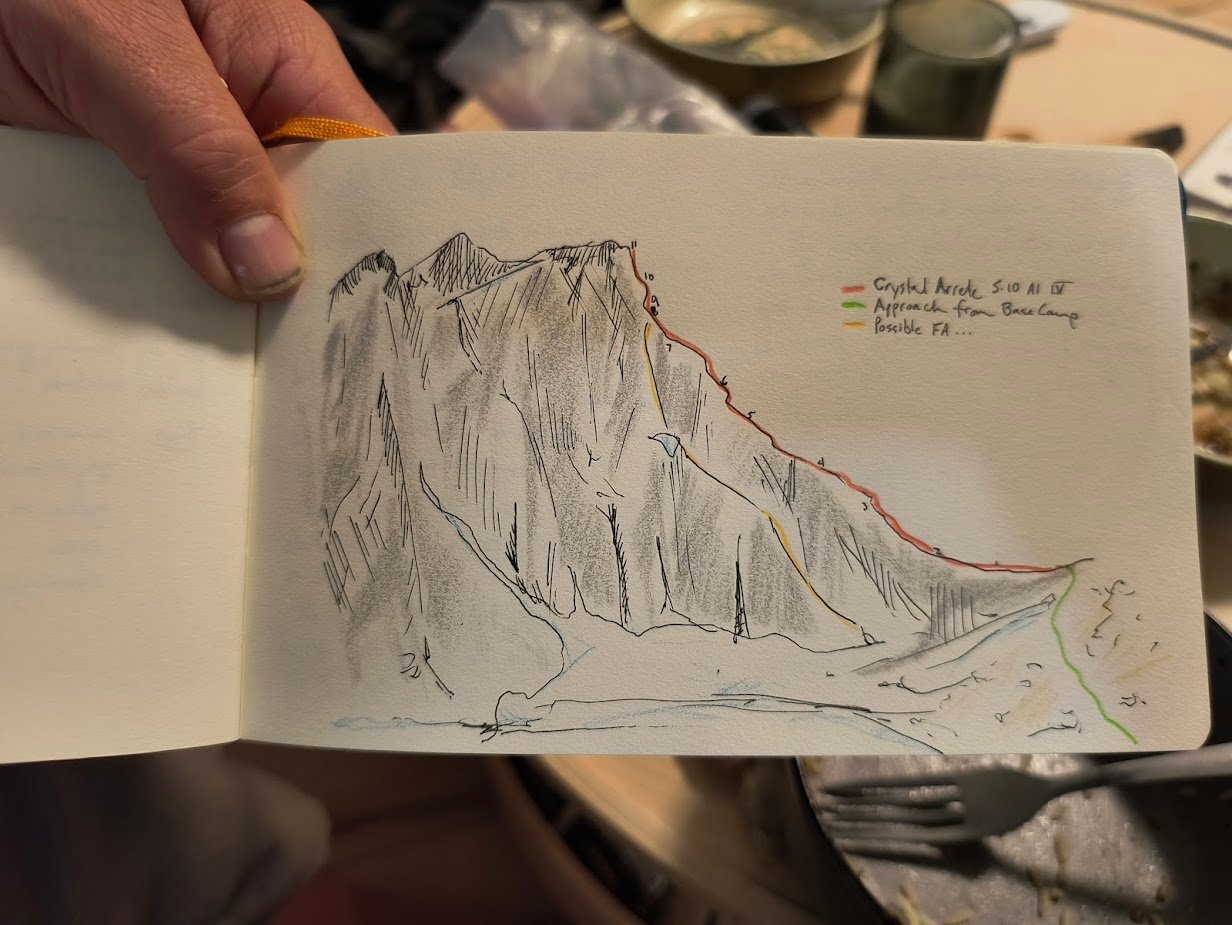

Dave’s sketch and topo of the route.